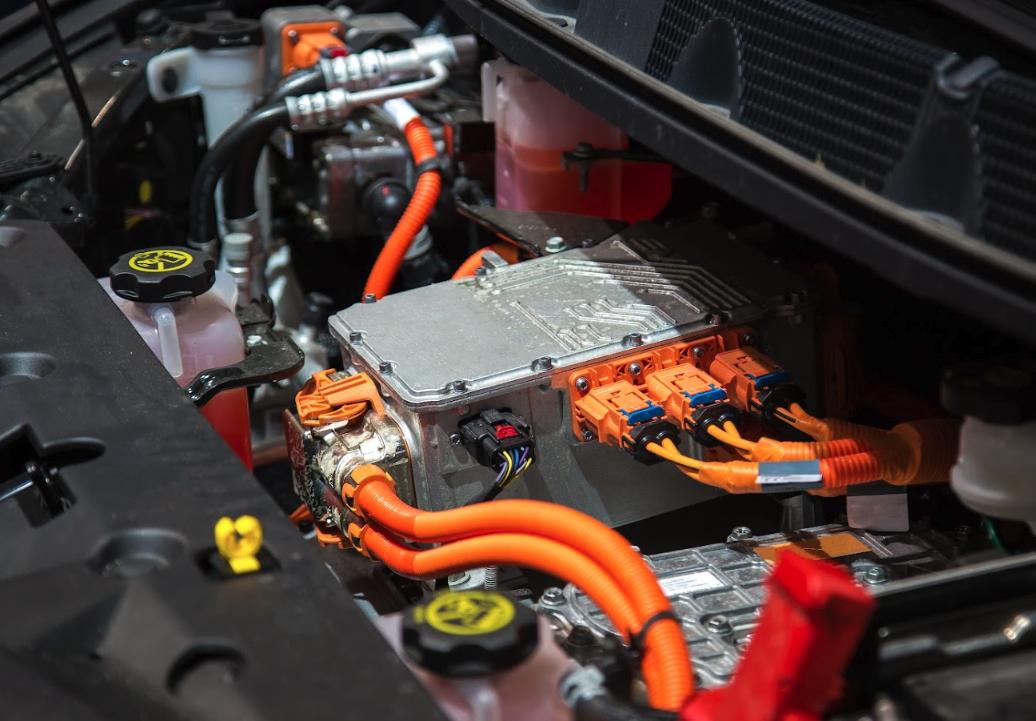

Batteries are found in many everyday objects (mobile phones, remote controls, electric vehicles), and are a means of storing energy so that you can have access to electricity even when you're far from a power socket.

However, their composition, manufacture and operation are not always obvious. In this article, we explain everything you need to know about how a battery works, starting with the basics: cells.

.webp)

Cells: the basis of a battery

The basic unit of a battery is a cell: the smallest element capable of storing electricity. They look like AA batteries - the ones in remote controls. A battery is therefore an assembly of several cells.

How does a cell work?

A cell stores electricity in the form of chemical potential energy.

When a cell is charged or discharged, chemical reactions (oxidation-reduction) create a flow of electrons: the electrical current. More precisely, the anode (the negative side when discharging) is oxidised, releasing electrons, and the cathode (the positive side) receives them. In a cell, these >electrode are connected to the terminals.

The electrons leave the anode to cross the charge connected to it and return via the cathode. Inside the cell, positive ions pass through the electrolyte in the same direction as the electrons. This way, the electrical charge on each side remains neutral, as the negative charge of the electrons and the positive charge of the ions cancel each other out.

.webp)

Discharging a cell causes the electrodes (anode and cathode) to go from a high energy level to a lower one. These reactions are, of course, reversible: if an electric current is passed in the opposite direction, the cell is recharged.

Here are the definitions of the technical terms used earlier:

- Oxidation-reduction: chemical reaction combining oxidation (releasing electrons) and reduction (absorbing electrons);

- Electrode: component on which redox reactions happen;

- Anode: oxidised electrode, producing electrons;

- Cathode: reduced electrode, receiving electrons;

- Electrolyte: substance capable of allowing ions to pass through, while blocking the flow of electrons.

Cell characteristics

Each cell has its own electrochemistry, defined by the materials that make up the anode and cathode. The cell's voltage depends on this chemistry: for example, cells with graphite and lithium iron phosphate (LFP) electrodes have a nominal voltage of 3.2 V. But when the state of charge varies, so does the voltage.

Each cell also has a capacity, measured in Ampere-hour (Ah). This value represents the amount of electrical charge the cell can store, and depends on the chemistry, the shape and size of the cell. Larger electrodes can store a higher charge. The charge of the battery is called the State-of-charge (SOC).

When you multiply the voltage by the capacity, you get the energy stored in the cell, in Wh. Note that this value is also called capacity, so it's important to specify the unit to avoid confusion.

Cells come in different shapes:

- Cylindrical: AA batteries or 18650 cells, found in electrically assisted bicycles (EABs);

- Rectangular: found in phones or Electric Vehicles.

.webp)

.webp)

Cells recharging and ageing

To recharge a cell, we apply a voltage between the electrodes, opposite in sign to the natural discharge voltage - more simply, we connect the battery to a power socket. This voltage must be higher than the discharge voltage. A current will then flow through the battery, driving the oxidation-reduction reactions in the opposite direction. The electrical energy will be absorbed by the cell to be used later.

Although rechargeable cells can be reused a large number of times, each discharge and recharge cycle damages the inside of the cell. This degradation leads to a drop in performance in terms of capacity and efficiency and an increase in internal resistance.

Cell arrangement

A battery is composed of one or several cells, associated in parallel and/or series,a to provide a certain amount of voltage, current and capacity.

When cells are arranged in series (positive to negative), their voltages are added together, producing one higher than a single cell could attain.

.webp)

When arranged in parallel (positive to positive, negative to negative), the capacity and current of the cells are added together.

Putting cells in series and in parallel produces a battery with the desired voltage, current and capacity, depending on its use.

Batteries are designated by the arrangement of their cells: xSyP, with x groups in series of y cells in parallel.

The Battery Management System (BMS)

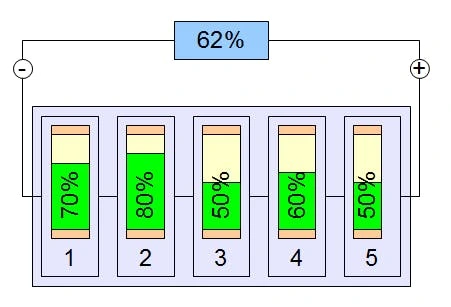

Not all cells are exactly the same: voltage, capacity and internal resistance may vary slightly from one cell to another. If we randomly combine them, cells or groups of cells can be discharged and recharged at different speeds. Over the long run, the battery will be partly overcharged and partly undercharged.

This phenomenon of cell imbalance is to be avoided: lithium cells in particular can overheat and be damaged as a result.

To avoid this imbalance, the BMS (Battery Management System) distributes the charge between the cells during a recharge, passing it from the overcharged cells to the undercharged ones.

The BMS also enables the SOC, temperature and voltage of each cell to be tracked, so that the battery's state of health can be monitored and any necessary action taken to extend its life. The quality of the BMS is just as important to the quality of a battery as the cells themselves.

References

Battery aging process, Part of the Philips Research Book Series book series (PRBS,volume 9)

Explore our resources

Stay informed about Bib's latest updates

Get technical content, use cases, and industry updates — tailored to your needs.

Want to know more?

Get in touch for more detailed information.