There are many types of Lithium-Ion battery, but 6 in particular stand out as the most common (and cited) types. They are the LFP, LCO, NMC, LMO, NCA and LTO batteries.

These acronyms are shorthand for chemical compounds, and generally (but not always) describe the material composing the cathode of the cells. For example, LFP stands for Lithium Iron Phosphate, which has the chemical formula LiFePO4.

Anodes are generally assumed to be made from graphite, but varying cathode chemistries yield great variations in performance.

Judgement criteria

There are multiple ways to characterize the performance of a Lithium-Ion cell, and they are all trade-offs of one-another.

LMO (Lithium Manganese Oxide)

Lithium Manganese Oxide cells were one of the first Lithium Ion chemistries created. They have fair energy density, high power, low cost and are quite safe. However, they suffer from poor cycle-life, as well as fast ageing in high-temperature conditions, relegating them to power tools and medical devices. Newer technologies are displacing this chemistry, which is expected to have a decreasing presence in the future battery market.

LFP (Lithium Iron Phosphate)

Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO4) cells are found in certain brands of electric vehicles. They are particularly well suited to places where weight or space aren’t at a great premium, such as large vehicles (RVs, forklifts, cherry-pickers, …). They are also useful in static applications: in conjunction with solar panels, for example.

This is due to this chemistries jack-of-all-but-one-trade profile: LFPs are generally safe, high-powered, low-cost, and long-lasting cells, with the only downside being low energy-density. If the space can be spared, then these cells make a good choice. The lack of heavier metals like nickel or cobalt make the cells comparatively non-toxic, but also lowers their value to the point of making recycling non-viable.

This chemistry is on the rise in EVs, and may become the most common one in the future.

NMC (Nickel Manganese Cobalt)

Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide cells (NMC) have dominated electric vehicle batteries due to their several advantages: somewhat low cost, decent lifespan, and the particular ability to be tuned for either high power density or high energy density.

NMC cells are named based on the proportion of each metal in the cathode: the most common, NMC 111, has equal proportions of all three, and has balanced characteristics. Other chemistries include greater proportions of nickel, and less cobalt (which is expensive). NMC 532, 622, and the experimental NMC 811 each have greater energy capacity and lower material cost than the last, at the cost of more difficult manufacturing and sensitive chemistry. Furthermore, these high-nickel compositions tend to have lower cycle-lives.

Valuable metals such as nickel and cobalt make recycling particularly interesting for these cells: our previous articles saw how this chemistry is usually the most sound economic choice for recyclers.

NCA (Nickel Cobalt Aluminium)

Nickel Cobalt Aluminium Oxide cells (NCA) have many of the up- and downsides of high-nickel NMC cells: great specific energy, lowered material cost when using less cobalt, high voltage, but also low cycle-life, low stability, and high manufacturing costs. NCA cells are also prone to thermal runaway, making them one of the more dangerous chemistries.

NCA cells are most famously used by Tesla (who also employ LFP cells), where their high capacity is most valuable.

LCO (Lithium Cobalt Oxide)

Lithium Cobalt Oxide cells are the ones most commonly encountered in our daily lives, as they are used in mobile phones and laptop computers. It was also the first Li-Ion chemistry patented and commercialized.

They have very high specific energy, but low power, suiting them well to low-powered portable applications. They are also quite unsafe, prone to thermal runaway when misused. Proper charging and cell management is a must. Their cycle life isn’t very good either, and well-used cells are at higher risk of overheating.

High cobalt content makes these cells costly from a materials perspective, dipping into a scarce resource, but a very mature technology means that these cells are some of the cheapest overall. The cobalt also means that toxicity is a risk, and their disposal must be done properly (as with all cells, but especially these ones).

LTO (Lithium Titanium Oxide)

The last cell type stands out because the chemistry involves the anode instead of the cathode. Instead of a simple graphite anode, Lithium Titanium Oxide (LTO) cells include titanium oxide crystals. This gives them very high power, great thermal stability, and a good lifespan, especially over long periods. Their cost remains very high, and their capacity low.

These cells are used in certain electric vehicles and in medical implants, where their high security and long life aspect become essential.

Other considerations

All this being said, sometimes cells aren’t so easy to describe, and information is often contradictory: LCO cells have been confidently described as both high in energy density, and also only average in that respect. LMO are either high-power, or moderate-power, depending on who’s writing. Safety is a difficult thing to quantify, or at least fairly abstract, using values such as negative temperature coefficients and thermal kinetics to describe risks. And environmental impact is a double-edged sword, where more toxic or rarer materials are more prone to proper recycling rather than disposal.

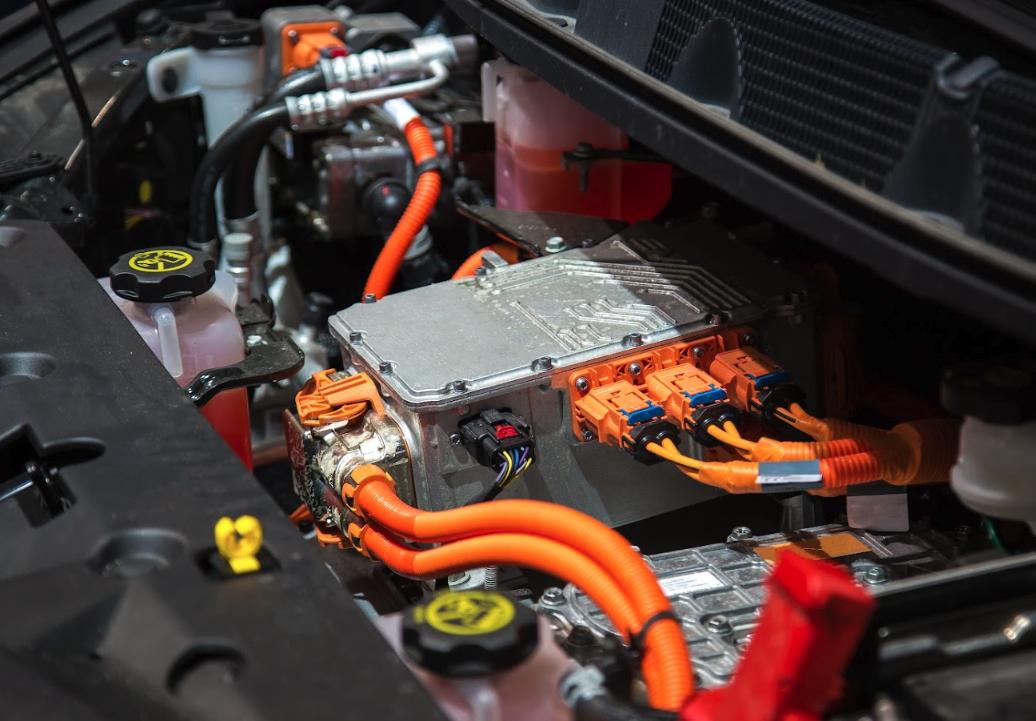

The chemistry of a cell is not the be-all-end-all of a battery: good BMS design will improve safety and extend the lifespan. A strong casing may reduce specific performance, in order to make handling safer. And usage will impact the life of a battery to a greater extent that the differences between chemistries.

The uses mentioned here aren’t set in stone either. Some electric vehicles employ LCO cells, preferring high capacity to long cycle life. Some phones use LFP cells, where the inverse logic applies. What cell you choose shouldn’t depend on what everyone else is doing, but what your needs and budget are.

Explore our resources

Stay informed about Bib's latest updates

Get technical content, use cases, and industry updates — tailored to your needs.

Want to know more?

Get in touch for more detailed information.