One of the reasons batteries are growing in popularity is the increasing demand for electric vehicles. Faced with the climatic impacts of using fossil fuels, more and more vehicles are replacing fossil fuels with battery power (about 100% year-on-year growth in sales). But what are the effects of using batteries instead? Are they really a less polluting alternative?

The question is difficult to answer, but let’s try here. We’ll look at the manufacture, lifetime usage and recycling of batteries, from the angles of energy, global warming impact, and materials.

What is the impact of battery manufacture?

The impact of energy demands

One of the first sides to look at is the amount of energy consumed by the production of a battery. It takes a lot of energy to extract and refine materials, transport them, and manufacture them into a battery. It can be spread out over the batteries a facility produces, and divided by their capacity to give a relative energy required in MJ/Wh. This energy can be averaged out over the battery capacity produced, and gives us a useful metric, the Cumulative Energy Demand, measured in MJ/Wh.

This study found a wide range of Cumulative Energy Demand, depending on the battery chemistry, but also the method of evaluation. But the average value found was 1.182 MJ/Wh. In other words (and units), it takes 328 Wh of energy to produce just 1 Wh of battery capacity!

.webp)

So, to produce a 640 Wh battery, the size you would find in an electric bicycle, would need about 756 MJ of energy, or about that contained in 20 L (5 gallons) of gasoline. The 100 kWh battery found in a large Tesla needs the equivalent of 850 gallons, or about 57 full refills of a gas-powered car. While these numbers don’t seem too big, they neglect the material requirements of batteries, so they’re not really comparable to gasoline usage.

On CED methodology

There is a large variance depending not only on the type of battery considered, but also the study methodology. 1.182 MJ/Wh is the average over all studies, but is not to be taken as an absolute. Energy demand is calculated either by dividing the total energy demand of a production facility among its battery operations (so-called ‘top-down’ method), or by following the batteries through a factory without considering the rest of the production (so-called ‘bottom-up’ method). The former produces higher estimates than the latter.

On fuel comparison

The 756 MJ of energy is that contained within 20 L of gasoline, not assuming any efficiencies or other losses. It’s merely illustrative. The figures that later compare batteries and fuels do however consider real-world usage data. It’s almost impossible to compare batteries to fuels due to their different natures: one a storage method, the other a chemical source. The numbers here are illustrative of energy cost. Think a big fire burning away to make a battery.

The impact of material costs

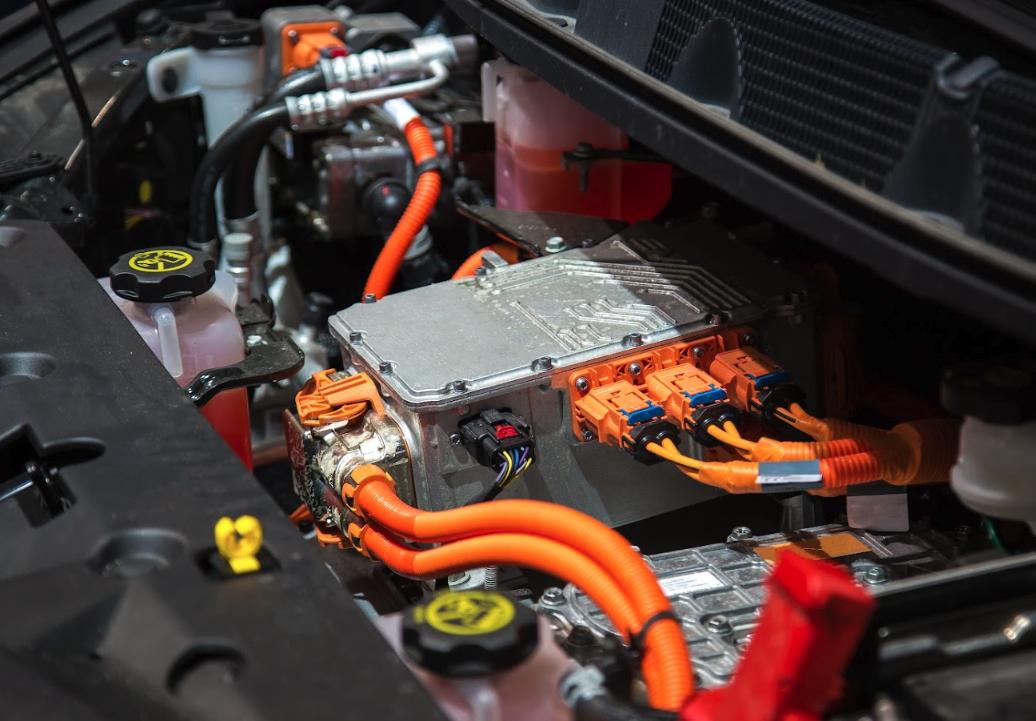

To build a battery, we need a few things: a cathode, an anode, electrolyte, a case, and various binder and support materials. All of these either have to be taken from primary sources (mining and refining) , or recovered from waste materials.

Of particular interest are the cathodes, which frequently contain oxides of cobalt, nickel, iron, copper, tantalum and manganese, and also the lithium itself. These metals are the result of mining, and need to be processed. All of this results in the depletion of non-renewable, inorganic resources.

.webp)

To summarize the cost as mere depletion would be unreasonable: resource mining has many other societal and environmental consequences. For example, the mining of cobalt and tantalum in regions such as the DRC and Rwanda have deeply negative effects (child labor, exploitation, pollution and degraded health), alongside the economic boons they can represent both for workers and the nations.

Abiotic depletion

The depletion of non-renewable, inorganic resources is called abiotic depletion, and is measured in equivalents of antimony. The methodology here (CML-rb) considers what can be extracted with current technology, not considering economics or total deposits on Earth. Tantalum actually isn’t used in cells, but rather the capacitors in the BMS. The BMS actually has a very strong weight in the materials and emissions of a battery!

Societal impact

The impacts of battery manufacture and resource extraction are wide reaching. The case of cobalt mining in the DRC serves as a stark example of the negative impacts brought about by the world’s hunger for rare minerals. That being said, the impacts on the world as a whole are very hard to quantify.

The impact of using the battery

Over their life, batteries will waste a certain amount of energy: even with high efficiencies of around 80% round trip (energy going in then coming out again), about 0.25 Wh of energy is used to store 1 Wh.

The ratio of energy restored over energy input from a battery is called the Round-Trip Efficiency.

Where do these losses come from? On one hand, converting electricity from AC to DC and back again, along with voltage conversions, causes some loss. On the other, the internal chemistry of the battery does not perfectly restore all that is put in. And finally, all the circuits and electrodes have some electrical heating losses.

Given that batteries have lifespans on the order of a few thousand cycles, their lifetime energy consumption really adds up. Our bicycle battery might have a lifespan of 1000 cycles. Charging and discharging it that many times will waste around 160 kWh, about a week’s worth of household energy in Europe.

Climate change effects

With all energy expenditure comes the implied consumption of fossil fuels, and the resultant greenhouse gas emissions and climate change potential. In Europe, producing 1 kWh of electricity emits around 230 gCO2e (grams of equivalent CO2) of greenhouse gasses (GHG).

Let’s look at our 640 Wh bicycle battery. It’s production needs 210 kWh of electricity, emitting 48 kgCO2e. If you were to use it for 1000 cycles, you would need to produce 800 kWh of electricity. This would emit around 184 kgCO2e, of which 37 are due to efficiency losses. The total is 232 kgCO2e. On a bicycle, this would get you about 50000 km of cycling. In a car, you would emit as much in a 2000 km trip. Anyone up for a ride?

When replacing gas-powered cars with electrical ones, a study has shown that that EV always comes out on top, in terms of lifetime GHG emissions. And as electricity production gets greener and more renewable, this scale tips ever further.

.webp)

We can summarize with this: batteries take a lot to make and operate. Lots of energy and materials, lots of CO2 and pollution. But when used right, notably when used alongside green energy and in carbon-offsetting roles, they more than make up for their costs. Like any technology, their sustainability depends on being used wisely.

Helping with proper use and prolonging the life of batteries is the raison d’être for BiB after all!

But what about when they can’t be used anymore? Tune in to see more in the coming articles.

References

[1] Jens F. Peters, Manuel Baumann, Benedikt Zimmermann, Jessica Braun, Marcel Weil, The environmental impact of Li-Ion batteries and the role of key parameters – review, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews

[2] Child miners: the dark side of the DRC’s coltan wealth. (2021), IssAfrica. last accessed 2022-05-05

[3] Datu Buyung Agusdinata et al, Socio-environmental impacts of lithium mineral extraction: towards a research agenda (2018) Environ. Res. Lett. 13 123001

[4] Benjamin K. Sovacool, When subterranean slavery supports sustainability transitions? power, patriarchy, and child labor in artisanal Congolese cobalt mining, (2021) Extractive Industries and Society

[5] Georg Bieker, (2021) *A GLOBAL COMPARISON OF THE LIFE-CYCLE GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS OF COMBUSTION ENGINE AND ELECTRIC PASSENGER CARS, The ICCT.

[7] [Global EV Market Up 105% YoY in January - Times Asia]

Explore our resources

Stay informed about Bib's latest updates

Get technical content, use cases, and industry updates — tailored to your needs.

Want to know more?

Get in touch for more detailed information.